Research Article

Pilot Telephone Intervention to Improve Survivorship Care in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer

Thanh P Ho1, Mary Jewison2, Kathryn J Ruddy2 and Katharine AR Price2*

1Department of Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA

2Department of Medical Oncology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA

*Corresponding author: Katharine AR Price, Department of Medical Oncology, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN, 55905, USA

Published: 01 Dec, 2017

Cite this article as: Ho TP, Jewison M, Ruddy KJ, Price

KAR. Pilot Telephone Intervention to

Improve Survivorship Care in Patients

with Head and Neck Cancer. Clin Surg.

2017; 2: 1795.

Abstract

Background: Multimodality treatment for Head and Neck Cancer (HNC) is associated with

significant impact on quality of life and underscores the importance of comprehensive survivorship

care.

Objective: A pilot phone intervention was conducted in HNC survivors to improve coordination of

care by addressing core problems: dysphagia, lymphedema, neck pain, fatigue, emotional distress,

financial concerns, and nicotine dependency.

Methods: Patients who had completed curative intent therapy for HNC were identified. One month

prior to an upcoming appointment, patients were called by a nurse who asked about common longterm

side effects and offered services and additional appointments as indicated.

Results: Forty-eight patients (38 males, 79%) with a median age of 60 years (range 41 to 78)

were contacted. Most were stage IVA HNC (34 patients, 92%), squamous cell carcinoma (44,

92%) and located in the oropharynx (28, 58%). Patients were contacted between 6 to 77 months

from definitive therapy, with conversations ranging from 3 to 30 minutes. Common symptoms

included neck pain (52%), dysphagia (46%), and lymphedema (19%). Fatigue (33%) and emotional/

psychological concerns (27%) were also noted. Financial matters (10%) and smoking cessation (4%)

were infrequently reported. Ultimately, 31% of conversations led to referrals or other interventions

resulting in a change in management.

Limitations: The sample size was small, and no direct patient outcomes were reported.

Conclusion: This study demonstrates the need for comprehensive and coordinated survivorship

care for patients with HNC.

Keywords:Head and neck cancer; Survivorship; Dysphagia; Lymphedema; Fatigue; HPV;

Oropharynx

Abbreviations

HNC: Head and Neck Cancer; HPV: Human Papillomavirus; HPV-OPC: HPV-Positive Oropharynx Cancer; IRB: Institutional Review Board; OS: Overall Survival

Introduction

Historically, Head And Neck Cancer (HNC) was associated primarily with tobacco and alcohol

use, with 40% to 60% Overall Survival (OS) rates for most patients with locally-advanced disease

[1-3]. However, in recent decades, the incidence of Human Papillomavirus (HPV)-associated

oropharyngeal cancer has been steadily increasing; in men in the United States, this is now the

eighth most common cancer [4]. The prognosis of HPV-Positive Oropharynx Cancer (HPV-OPC)

is significantly better, with three year OS in never-smokers approximately 90% [5]. In addition,

patients with HPV-OPC are typically younger, healthier, and have less history of tobacco use than

patients with HPV-negative HNC. As a consequence, patients with HNC are being cured at higher

rates and most will be expected to live decades with treatment-related side effects. Treatment for

locally-advanced HNC typically involves a combination of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy.

This multimodality therapy is associated with long-term treatment-related side effects such as

xerostomia, dysphagia, pain, lymphedema and fatigue.

Improved survival rates for many patients with HNC combined with substantial treatment morbidities create a need for comprehensive survivorship care for this patient population. In elderly patients with laryngeal squamous cell

cancer, higher quality care has been associated with both improved

survival and reduced cost [6]. One challenge in clinical practice is

to identify and offer referrals to manage long-term side effects in

an efficient and coordinated fashion. In October 2013, Mayo Clinic

in Rochester, Minnesota began an HNC survivorship initiative to

better address the needs of these patients. A multi-disciplinary team

of clinicians compiled an extensive list of survivorship issues with

potential interventions. Of the 52 clinician-identified survivorship

issues, seven were chosen to be addressed in a clinical phone pilot

based on the fact that 1) They are common problems in clinical

practice and 2) established clinical interventions or referrals exist

to address these issues. Theses even survivorship issues included:

dysphagia, lymphedema, neck pain, fatigue, financial concerns,

emotional distress, and nicotine dependency.

At this comprehensive cancer center, standard follow-up care

after completion of treatment for HNC includes multidisciplinary

follow-up with otolaryngology-head and neck surgery, radiation

oncology, and medical oncology visits every three months for the first

two years after treatment, then every six months for three years, and

then annually after five years. These appointments offer point-of-care

opportunities to intervene on long-term side effects of treatment. In

the current practice, many patients travel from distant locations for

follow-up care, and it can be challenging to get appointments at short

notice when an active issue is identified during the clinic follow-up

visit. In February 2014, a phone pilot was initiated to proactively

identify symptoms prior to a patient’s appointment, with the focus

ondysphagia, lymphedema, neck pain, fatigue, financial concerns,

emotional distress, and nicotine dependency. The goal of the phone

pilot was to improve coordinated survivorship care. This manuscript

reports the results of this clinical phone pilot.

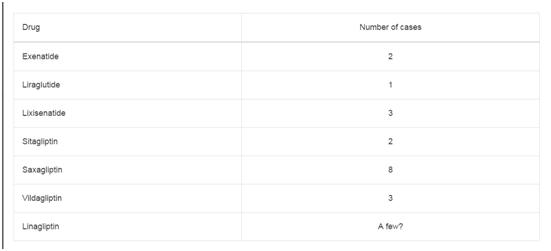

Table 1

Methods

The phone pilot was conducted by a dedicated HNC nurse in the Division of Medical Oncology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. Patients were identified for the pilot based on the following criteria 1) Had completed definitive (curative-intent) therapy for a HNC and 2) Had a follow-up appointment scheduled in medical oncology within one month after the pilot phone call. During the phone call, the nurse inquired about the patient’s overall health status and asked specifically about the seven above-specified target areas. A data collection sheet was completed at the time of the phone call that documented patient responses to the target questions and whether the phone call resulted in any additional appointments, referrals, or other actions. Additional data such as cancer stage and therapy were abstracted from the electronic medical record using retrospective chart review. The study was approved by the institution’s Institutional Review Board (IRB). Descriptive studies were performed using JMP® (Carey, North Carolina).

Results

Demographics: Forty-eight patients (38 males, 79%) were

contacted; the majority were white (47 patients, 98%; Table 1). Over

half (27 patients, 56%) did not have a significant smoking history. The

median age at diagnosis was 60 years (range 41 to 78). The median

time since definitive treatment was 21 months (range 6 to 77 months).

Cancer characteristics: The majority of patients were stage IVAHNC (34 patients, 92%; Table 1), predominantly squamous

cell carcinoma (44 patients, 92%) and located in the oropharynx

(28 patients, 58%). Human Papillomavirus (HPV) positivity, per

pathologic staining for antibodies to p16 or HPV in-situ hybridization

studies, was reported for 19 patients (68%) with oropharyngeal

squamous cell carcinoma. Most patients received surgery (62%),

radiation (98%), and systemic therapies (96%).

Pilot intervention: Phone conversations lasted 10.37 ± 7.13

minutes on average (median 7 with range from 3 to 30 minutes).

Thirty-seven individuals (77%) expressed concern about at least one

topic (Table 2). This led to 15 referrals or other interventions (31% of

conversations) with 10 messages sent to providers in other disciplines

(21%) and 8 changes in upcoming appointments (17%).

Neck pain or stiffness was reported by over half of patients (25

patients, 52%); six of them received interventions including referrals

to cancer rehabilitation or physical medicine and rehabilitation, or

resources on acupuncture. Two who did not receive interventions

had previously tried acupuncture or massage therapy without

significant benefit. Lymphedema was a concern for 9 patients

(19%), although many also reported that their lymphedema was

improving. Concern over lymphedema resulted in 1 intervention

(2%), a referral to cancer rehabilitation that included consultation

with a lymphedema therapist. Another patient had previously been

evaluated by a lymphedema specialist. Of the 25 individuals with neck

pain or stiffness, 6 patients also had difficulty with lymphedema.

During these phone conversations, 22 patients (46%) reported

difficulty swallowing, resulting in 4 interventions that included

prescription for Biotene® as well as patient-specific resources on

acupuncture. Two patients already had scheduled endoscopy and

swallow study, respectively, at the time of phone call.

Patients also expressed a range of psychological and emotional

concerns (13 patients, 27%) including anxiety, depression, anger,

cognitive changes related to memory, issues with self-esteem or the

workplace. This resulted in 7 interventions (15%). Support groups,

stress management brochures, and referrals to psychiatry or social

work were offered. Two declined interventions and preferred to

discuss their concerns with their oncologist or primary care physician

instead. Similarly, energy level was a concern for 16 patients (33%),

with 2 (4%) receiving pamphlets on potential solutions tailored to

specific patient interest, such as yoga or tai chi. Six patients (13%)

endorsed both fatigue and psychosocial concerns.

Less commonly, patients reported financial concerns (5 patients,

10%); no interventions were performed. One patient opted, instead,

to discuss these issues during his medical oncology follow up

appointment. Two patients (4%) expressed difficulty with smoking

dependence; one was offered nicotine cessation clinic and the other

was already utilizing nicotine patches to reduce nicotine use.

These phone calls encouraged patients to discuss other medical

concerns as well; for instance, one resulted in physical therapy referral

for shoulder pain (without reporting neck pain). In another instance,

the nurse spoke with the patient’s spouse, who was “extremely happy

to get the call”, and agreed to receive educational materials by mail.

Table 2

Discussion

HNC survivors who undergo multidisciplinary therapy may

experience significant treatment-related side effects that can impact

quality of life. Individuals with late-stage tumors report significantly

worst quality of life scores on areas such as swallowing and social

contact [7]. Long-term overall quality of life can decline, as reported

by a study on 10-year survival [8]. We present a telephone-based pilot

intervention to address common side effects experienced by HNC

survivors. Our study demonstrates that even for patients several years

from definitive treatment, symptoms such as dysphagia and neck pain

often persist. The challenges of assessing and treating dysphagia may

contribute to this [9]. We found that a medical oncology nurse-based

phone call helped to identify patients with specific symptoms (usually

related to radiation or surgery) for which targeted interventions (e.g.,

endoscopy or physical medicine and rehabilitation) could be helpful,

it not already scheduled.

Our pilot intervention also identified and addressed important

psychosocial concerns in HNC survivors. We found that fatigue,

anxiety, and/or depression, present in nearly a third of all participants

and often persist long after completion of treatment. Poor body image

among this cohort can contribute to depressive symptoms [10], and

individuals with HNC, especially those with cancer of the larynx

and hypopharynx, are at increased risk of suicide [11]. It remains

unclear if psychosocial factors contribute to survival, and others

studies have attempted to assess this association or predict survival

based on quality of life scores [12,13]. It is apparent, by our study and

others, that psychological distress is common in this unique patient

population but may be under-recognized or undertreated [14].

This pilot study underscores the importance of coordinated,

multidisciplinary survivorship care. Many of the concerns that were

reported by these HNC survivors are best addressed by non-oncology

specialties including primary care providers, gastroenterologists,

physical medicine and rehabilitation specialists, and psychiatrist/

psychologists. In addition, the effectiveness of this phone pilot

highlights the value of patient contact that is not necessarily a faceto-

face evaluation. Although a telephone-based nursing assessment

does require staff resources, the average length of each phone call was

only ten minutes. It is notable that 31% of the phone calls resulted in

a tangible change to a patient’s upcoming appointment schedule. In

the future, it is possible that text- or web-based communication could

serve a similar purpose.

The primary limitation of this study was its small sample size.

In addition, no direct patient-reported outcomes were collected due

to limited resources. Therefore, we were not able to compare this

telephone-based intervention to standard care with regard to patient

satisfaction and physical and mental quality of life. However, this

hypothesis-generating study did have a wide age range of patients

with HNC, from 41 to 78 years old, suggesting that our findings are

reasonably generalizable across the age spectrum. Due to the size of

the study, sex-specific analysis was not performed. With improving therapies that may prolong life in HNC, survivorship care should

address therapy-related side effects in addition to the impact of

emotional and psychological challenges of cancer treatment. In light

of rising numbers of cancer survivors, the future of survivorship care

will likely involve utilizing resources such as phone interventions

and web-based programs to provide comprehensive, coordinated

survivorship care.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Julie Schutte, R.N., O.C.N.; Pearl Pham, P.A.-C.; Jessica Brandt, R.N., O.C.N. and Sadie Flatt, R.N. for their assistance with clinical care and coordination of care on this study.

References

- Calais G, Alfonsi M, Bardet E, Sire C, Germain T, Bergerot P, et al. Randomized trial of radiation therapy versus concomitant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for advanced-stage oropharynx carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(24):2081-6.

- Forastiere AA, Goepfert H, Maor M, Pajak TF, Weber R, Morrison W, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy for organ preservation in advanced laryngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(22):2091-8.

- Adelstein DJ, Li Y, Adams GL, Wagner H Jr, Kish JA, Ensley JF, et al. An intergroup phase III comparison of standard radiation therapy and two schedules of concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with unresectable squamous cell head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(1):92-8.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):7-30.

- Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, Weber R, Rosenthal DI, Nguyen-Tân PF, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):24-35.

- Gourin CG, Starmer HM, Herbert RJ, Frick KD, Forastiere AA, Quon H, et al. Quality of care and short- and long-term outcomes of laryngeal cancer care in the elderly. Laryngoscope. 2015;125(10):2323-9.

- Chaukar DA, Walvekar RR, Das AK, Deshpande MS, Pai PS, Chaturvedi P, et al. Quality of life in head and neck cancer survivors: a cross-sectional survey. Am J Otolaryngol. 2009;30(3):176-80.

- Mehanna HM, Morton RP. Deterioration in quality-of-life of late (10-year) survivors of head and neck cancer. Clin Otolaryngol. 2006;31(3):204-11.

- Schindler A, Denaro N, Russi EG, Pizzorni N, Bossi P, Merlotti A, et al. Dysphagia in head and neck cancer patients treated with radiotherapy and systemic therapies: Literature review and consensus. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2015;96(2):372-84.

- Rhoten BA, Deng J, Dietrich MS, Murphy B, Ridner SH. Body image and depressive symptoms in patients with head and neck cancer: an important relationship. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(11):3053-60.

- Kam D, Salib A, Gorgy G, Patel TD, Carniol ET, Eloy JA, et al. Incidence of Suicide in Patients With Head and Neck Cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141(12):1075-81.

- Mehanna HM, De Boer MF, Morton RP. The association of psycho-social factors and survival in head and neck cancer. Clin Otolaryngol. 2008;33(2):83-9.

- Osthus AA, Aarstad AK, Olofsson J, Aarstad HJ. Health-related quality of life scores in long-term head and neck cancer survivors predict subsequent survival: a prospective cohort study. Clin Otolaryngol. 2011;36(4):361-8.

- Neilson K, Pollard A, Boonzaier A, Corry J, Castle D, Smith D, et al. A longitudinal study of distress (depression and anxiety) up to 18 months after radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22(8):1843-8.